I’ve been making only slow and occasional progress on the Australian Sailfish. Home improvement projects, interspersed with periods of nursing my persistent malaise, interspersed with acquainting myself with a new camera on local, morning jaunts, and a comic book cabinet project I’m doing for a friend, have intervened. Further, what little progress I’ve made I simply haven’t documented, or I documented it but didn’t bother to upload it here. So let’s do some catch-up.

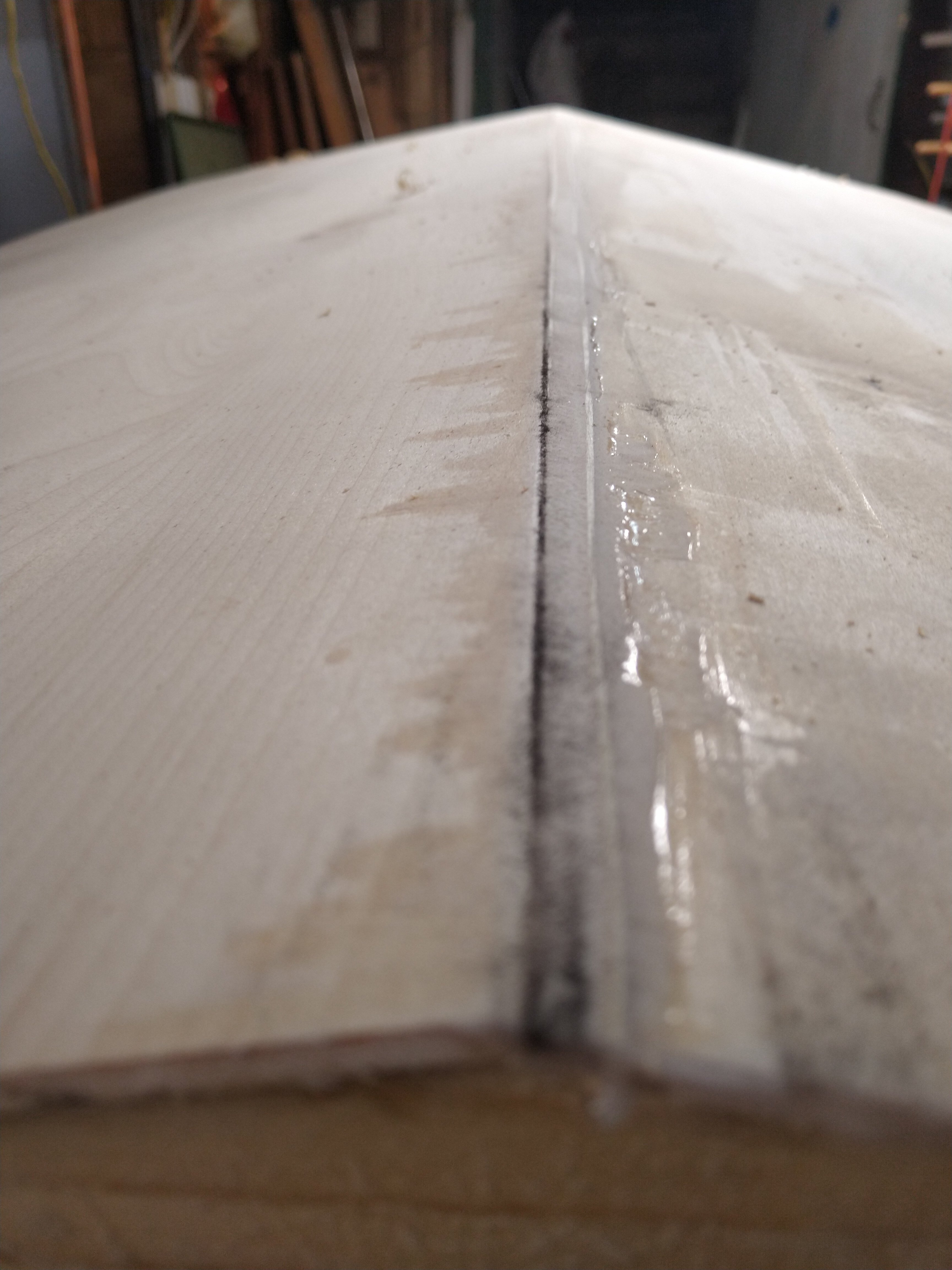

First, I managed to get the bottom on. This was fussy, and the results were not spectacular. Something I was afraid of happened: the bevel on the keel wasn’t really coplanar with the angle of the stations. Either the drawings had me cutting too deep of a notch on the stations for the keel to set in, or my stock was too thin, or I inadvertently planed it down too far. As a result, the two bottom pieces didn’t meet cleanly and I had to save it by filling with thickened epoxy. If I had wanted an unpainted bottom this would have been a deal breaker. But then, if I had wanted an unpainted bottom then I would have butted the two halves, not lapped them.

So here I have the ugly bevel. And when I’d mostly established center, I went ahead and cut the daggerboard slot. Then I ran a chalk line and tuned the bevel to run straight along it.

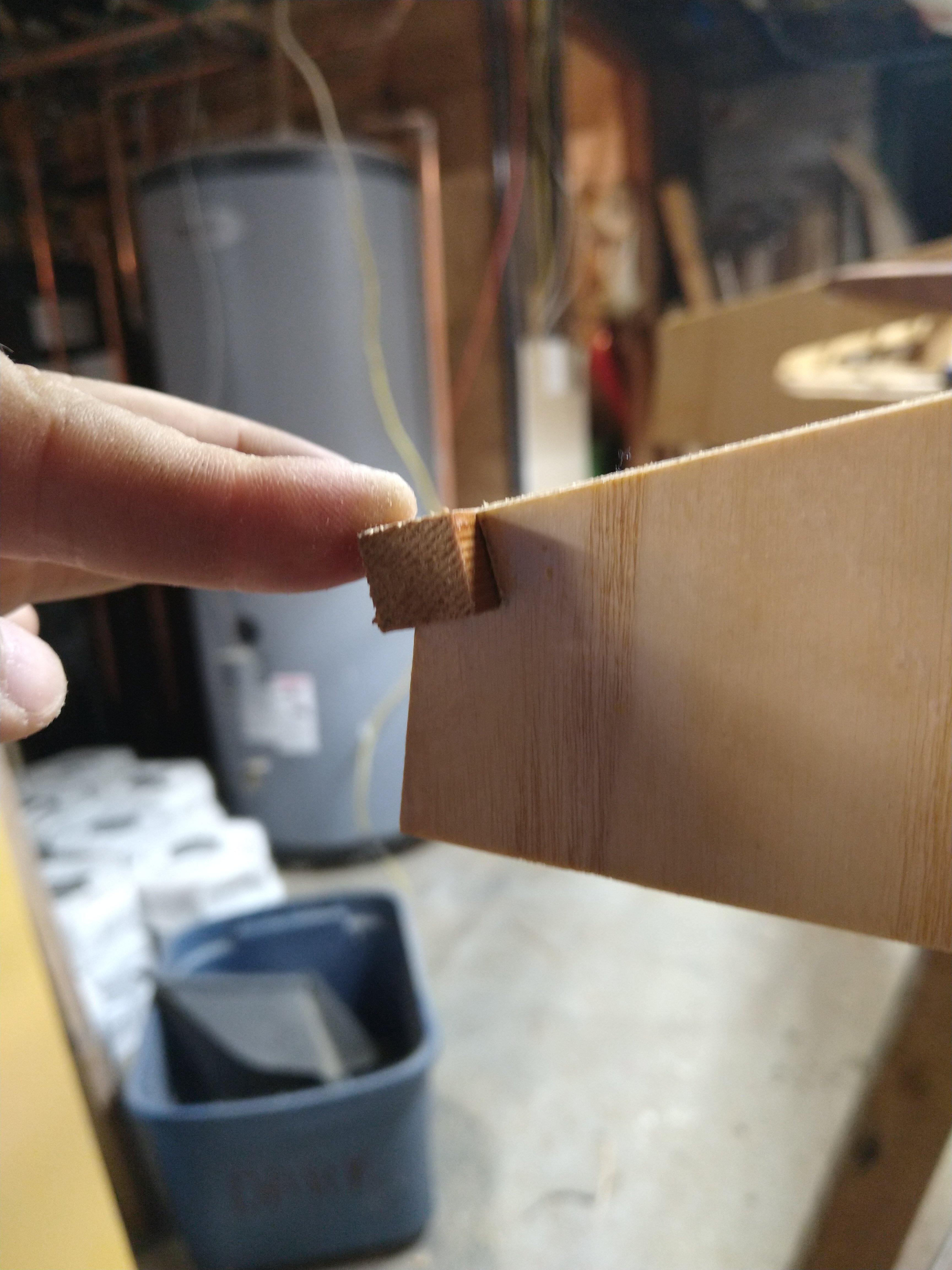

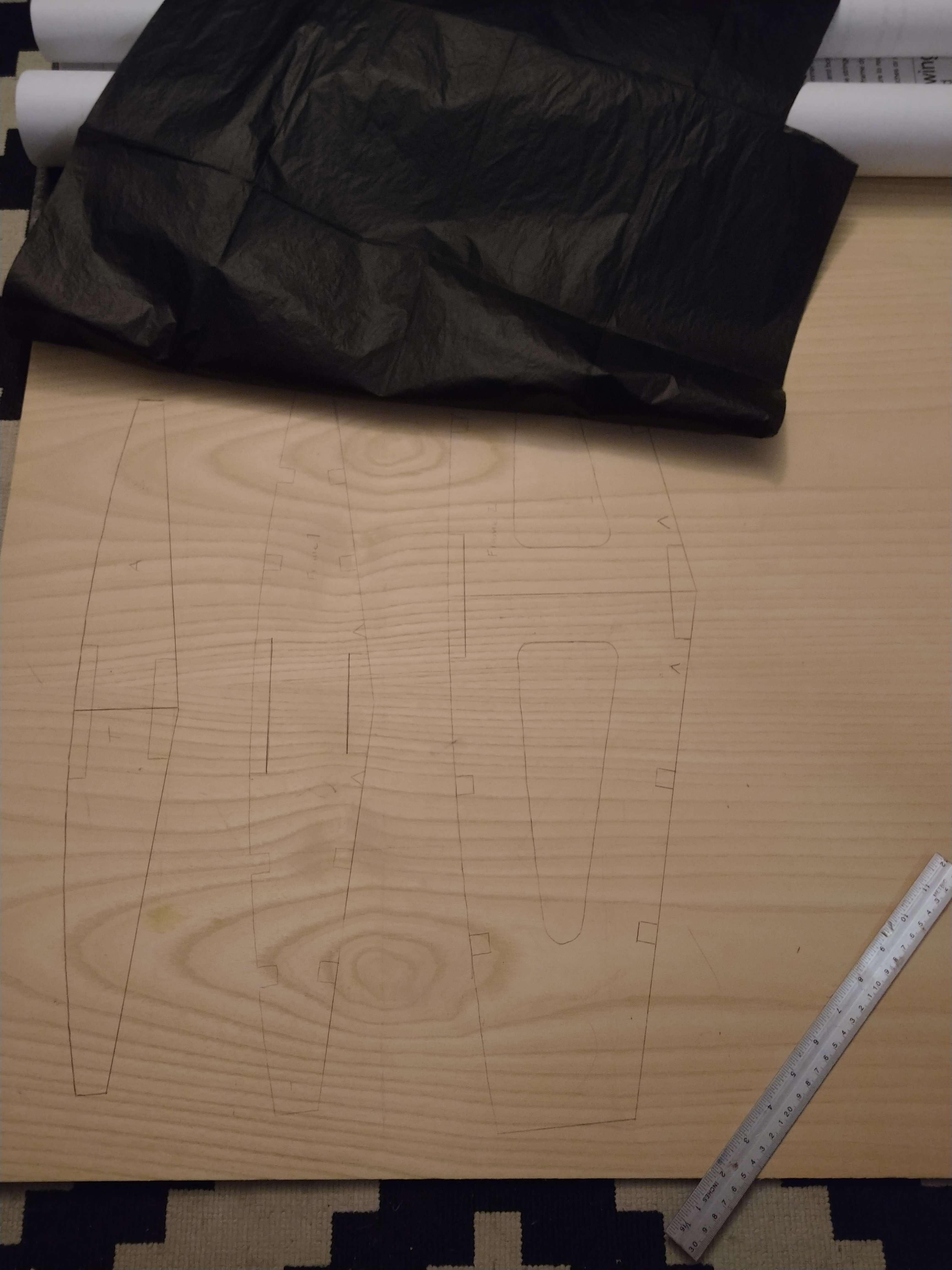

So now it’s time to fit the interior out for hardware. I chose to put T-nuts everywhere, so I can add the hardware after putting the deck on. I chose to laminate squares of the ply, rather than use blocks of cedar, just because that seems a better use of scrap material.

In the bow, I installed bolts where I’ll install a U channel to hold the forestay.

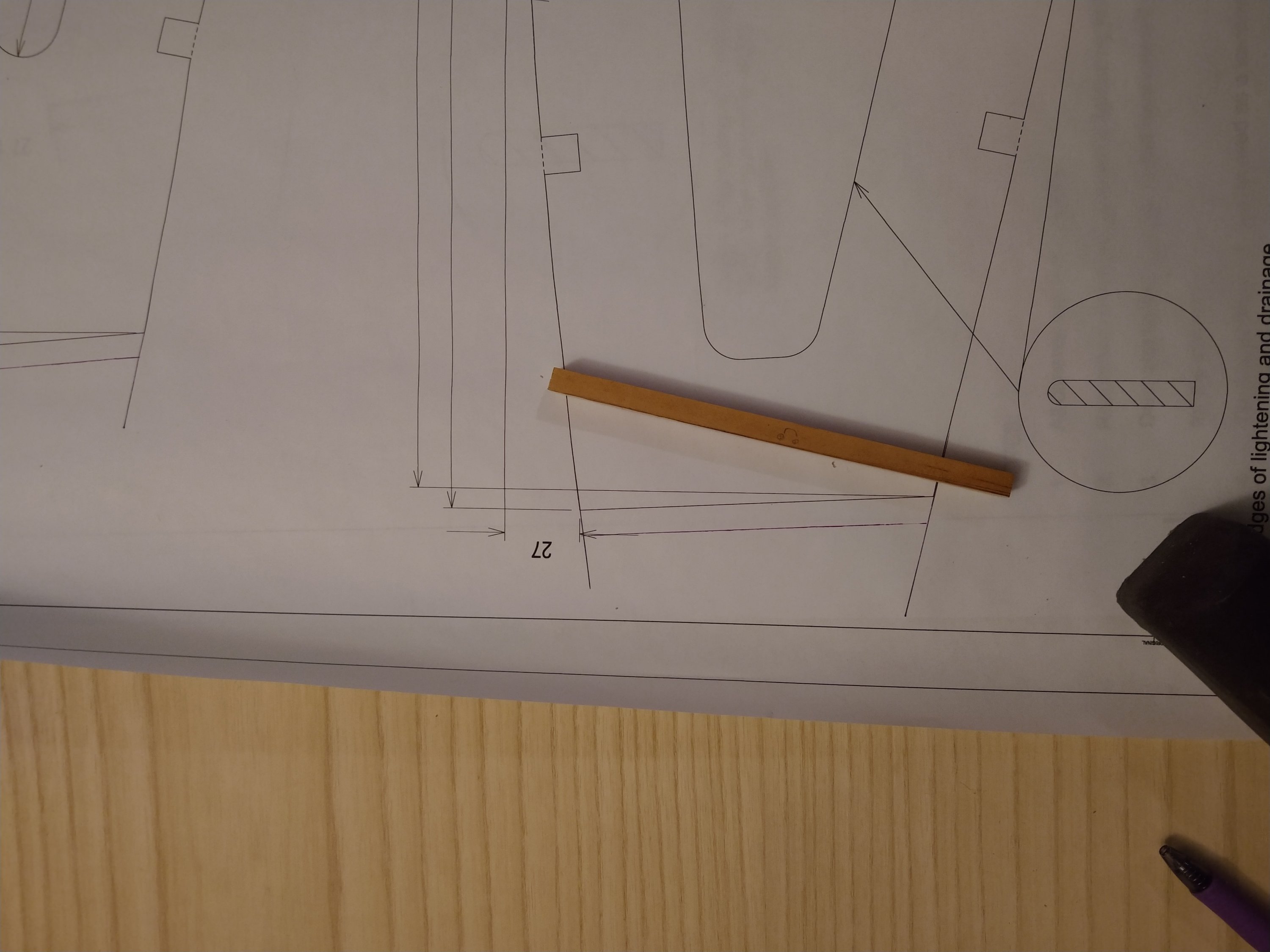

On the sides, I installed bolts for the shrouds. These are at an angle specified in the plans. After drilling out the bolt holes I pressed the T-nuts into the wood. Then I removed them so I could coat the entire assembly with unthickened epoxy. Once tacky, I added the T-nuts back in.

The transom was fussy, because of how I had to work between the deck and the keel plank. And because I’m paranoid about the rudder, I made the backing plate three layers thick of ply. But this was too much as the bolts I bought weren’t long enough. Silly mistake. Since I didn’t want to bother getting new bolts I just chiseled out a recess. I got it done, but it wasn’t pretty.

Next step is to go back to the epoxy. I’ll be spending the next little while cleaning op and filleting the stringers and all other joints. I have to do this now, because the next step is the deck stringers, and once they’re in I’ll be severely restricted in my ability to access the awkward corners.